Drawing on the Past and the Present

with Georgia on my mind

Thanks for being here! If you’re not already, please consider subscribing.

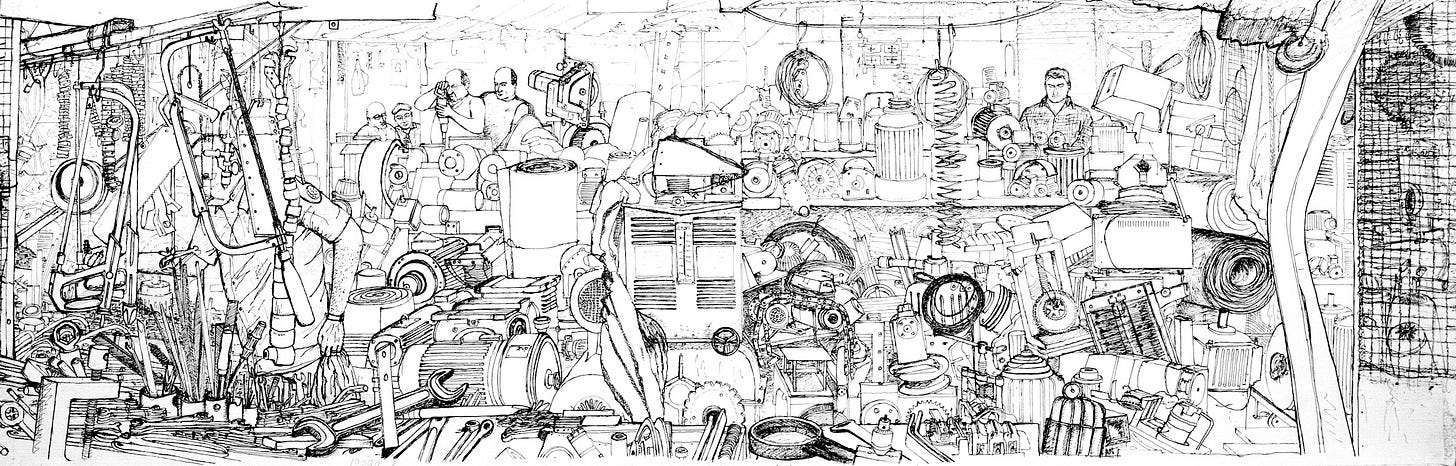

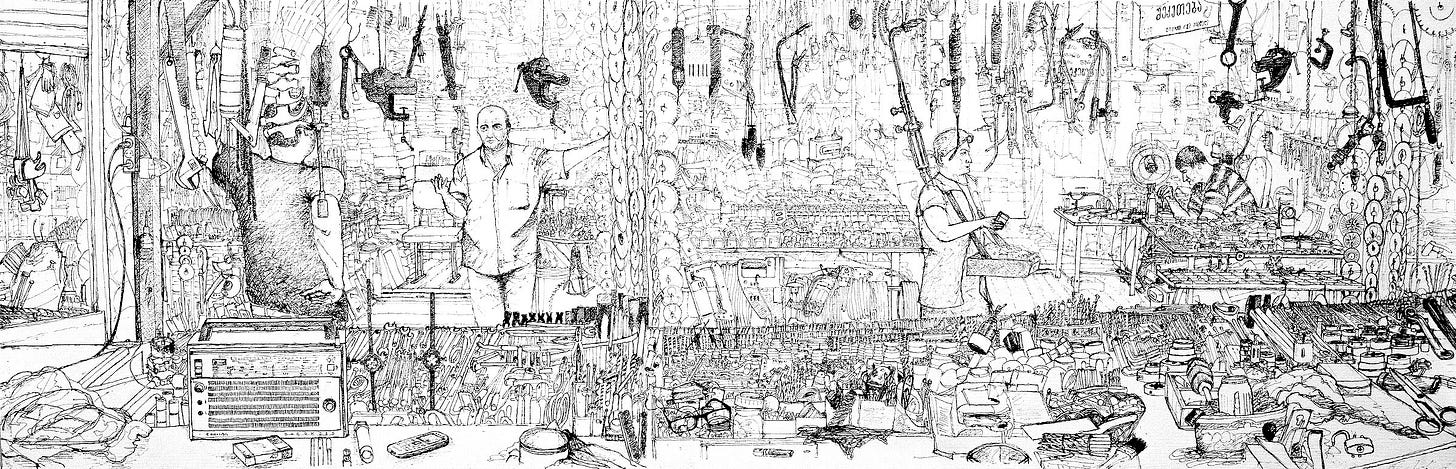

Ten years ago, I did a big drawing (4m long) of a small space in this open-air market in Tbilisi, Georgia, which sold Soviet-era tools and machinery. This is one section of it.

It was a crazy idea. I doubt I’ll ever do anything like it again.

But back then, I was drawn, no pun intended, by the challenge of depicting this intricate place, crammed with hard metal and the soft tissue of human life.

I was also starting to experiment with using sketching and art for journalism. And I was intrigued by the story of this second-hand hardware bazaar and the people working there.

It was a microcosm of the sharp and violent pendulum shift the country had undergone since the collapse of the Soviet Union, creating new winners and losers, as well as a new strain of tribalised politics.

Known locally as the Eliava, the market had been born in Georgia’s turbulent early 1990s, when the elation of independence from the USSR had given way to economic ruin and civil war. Everything was reused then; there was no money for new.

Twenty five years later, Georgia was in better shape. It had embraced democracy and the free market, and was hoping the West would reciprocate by admitting Georgia into its military and economic clubs—fearful of being dragged back into Russia’s orbit.

But Moscow wasn’t done with Georgia. In 2008, it had briefly invaded to stall that embrace. Its gravitational pull had only ebbed rather than ended.

And in the Eliava, many of the stallholders and market workers were conflicted, unsure or unhappy about their country’s path.

Everyone I drew had grown up under Soviet rule. Some wished it had never ended. Some were just more comfortable with what they knew best.

Some blamed the West for their troubles, in effect accusing it of starting a culture war on their traditions.

Democracy and capitalism had brought “anarchy and filth”, one trader complained. Georgia’s Orthodox Christian values were endangered by “Western ideas” like LGBTQ rights, he said, a refrain that would become increasingly common.

Many others expressed similar sentiments.

For a better view of the drawing, try this interactive multi-media version. It includes embedded interviews with the people I drew, as well as the back story. Give it time to load.

There were fewer customers for their old tools and machines by 2015. New stores and businesses were encroaching around the edges of the original market.

This free market selling the communist past was supposed to have been a mid-way station to something better. Instead, it had become the end of the line for many working there, leaving some bitter and disillusioned.

Meanwhile, developers were already eyeing up the Eliava’s prime location along the riverfront in Tbilisi.

Today, dozens of the original stalls have closed and the market’s days look numbered, with talk of moving it elsewhere.

So the drawing is already a kind of historical record.

Yet the story the traders embodied then is still relevant. Because, as events in Georgia over the past year have shown, the battle for its soul and direction, pulled between the West and the East, is far from over.

And, as it has turned against the West, the ruling party and its backers have made ‘family values’ and the ‘LGBTQ threat’ a centrepiece of their campaigns, mimicking the tactics of other political operatives elsewhere.

The world may seem divided at times. But it is striking how united it has become in how to achieve it.

Ten years ago, I set out to tell a story through a drawing. I stumbled across a frontline in the global culture war as well.

always loved that drawing, and interesting how it connects not only to the past but to something that is very present...

A Bayeux Tapestry for Tbilisi! Don't stop drawing. Or reporting. Or the two together - a new spin on journalism to challenge iPhone passer-by recorders of the news...