Drawing Afghanistan (part 1)

A sketchbook tour of a country in war while hoping for peace (1/2)

For this latest of two illustrated posts, I’m pulling together some of my drawings from periods I spent reporting from Afghanistan over the past two decades.

About 15 years ago, I started doing sketches of places and people I encountered in the course of my reporting.

At first, they were quick pencil or biro drawings in my notebook. Then I graduated, so to speak, to a separate sketchbook, ink pens and a watercolour pad, before publishing pieces combining text and drawings. I hoped it would be a way to reach different audiences for some of the issues I was covering. And one of the first places I trialled this approach from was Afghanistan, from where I spent many years reporting.

This first set of drawings covers the period of the 2001-2021 US occupation. I’ll do a second post covering trips I made after the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021. Many of these drawings are in my book on Afghanistan, in black and white.

I first arrived in Kabul just after the US and its Afghan allies had ousted the Taliban in 2001 and the city was a scene of devastation, a legacy of the civil war that ravaged the country in the decade before.

The ruined Darulaman Palace—built in the early 20th century after Afghanistan gained its independence from Britain—had become one of the monuments to this dark period in Kabul’s history, when at least 50,000 people were killed.

The palace was later rebuilt but the failure by the US and its partners to pay heed to the lessons of that civil war sowed the seeds for the Taliban’s return.

In the early 2000s, this wrecked Soviet tank occupied a commanding position near the tomb of Ahmad Shah Massoud, who won fame for resisting first the Soviet invasion and then the Taliban from his home base in the Panjshir valley, north of Kabul. Massoud was assassinated two days before the September 11 terrorist attacks by Al Qaeda agents posing as journalists.

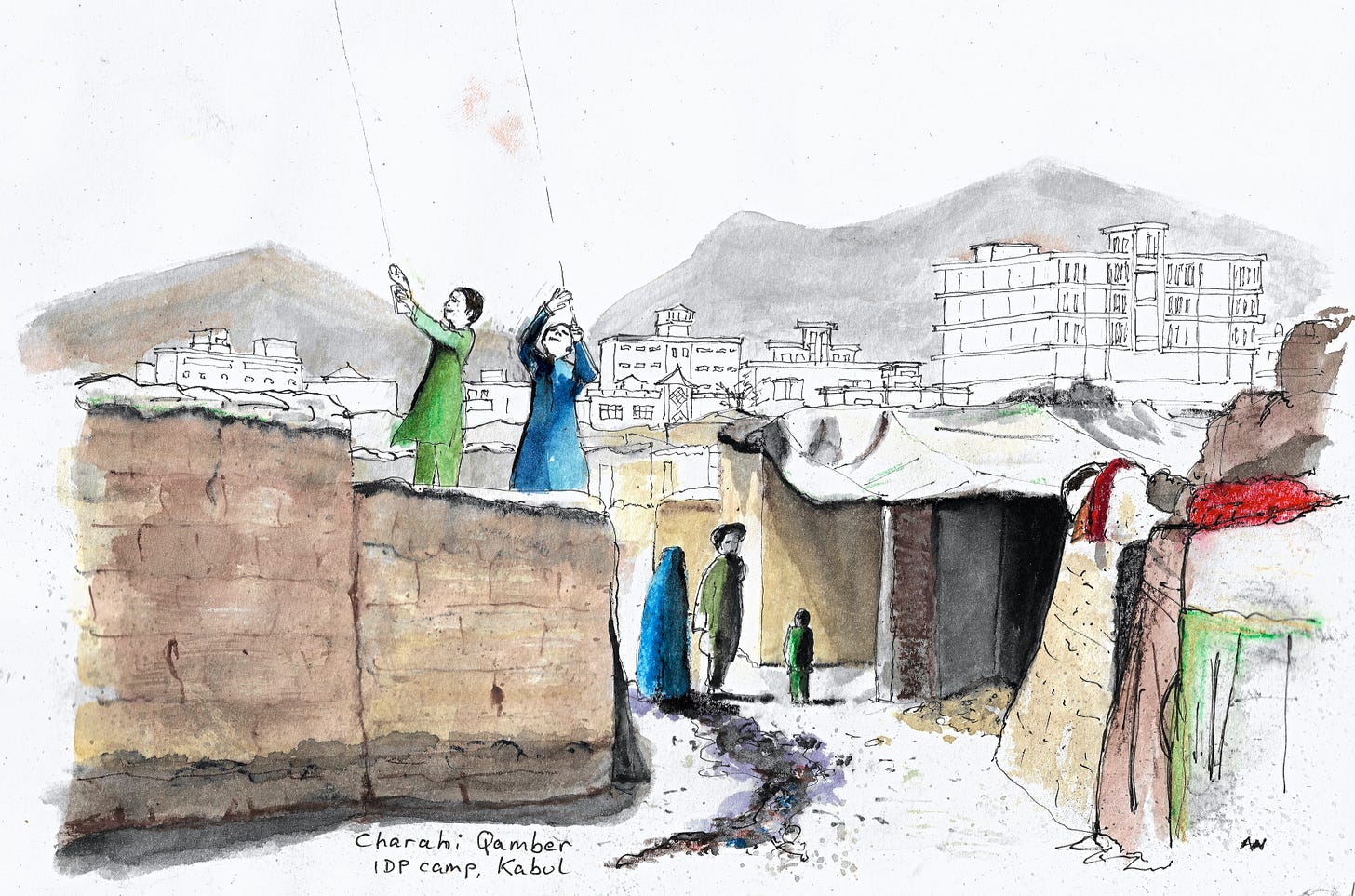

By the mid-2010s, hundreds of thousands of people displaced by the US-led war against the Taliban in the south and east had fled to Kabul, creating suburban shantytowns in the midst of a construction boom. In Afghanistan, war and peace have always co-existed. This settlement was dominated by people from Helmand province.

Thanks for being here and supporting my work. This one is free to read, but for just $6 a month you get all my writing and sketchbook reporting. Your generosity keeps this going.

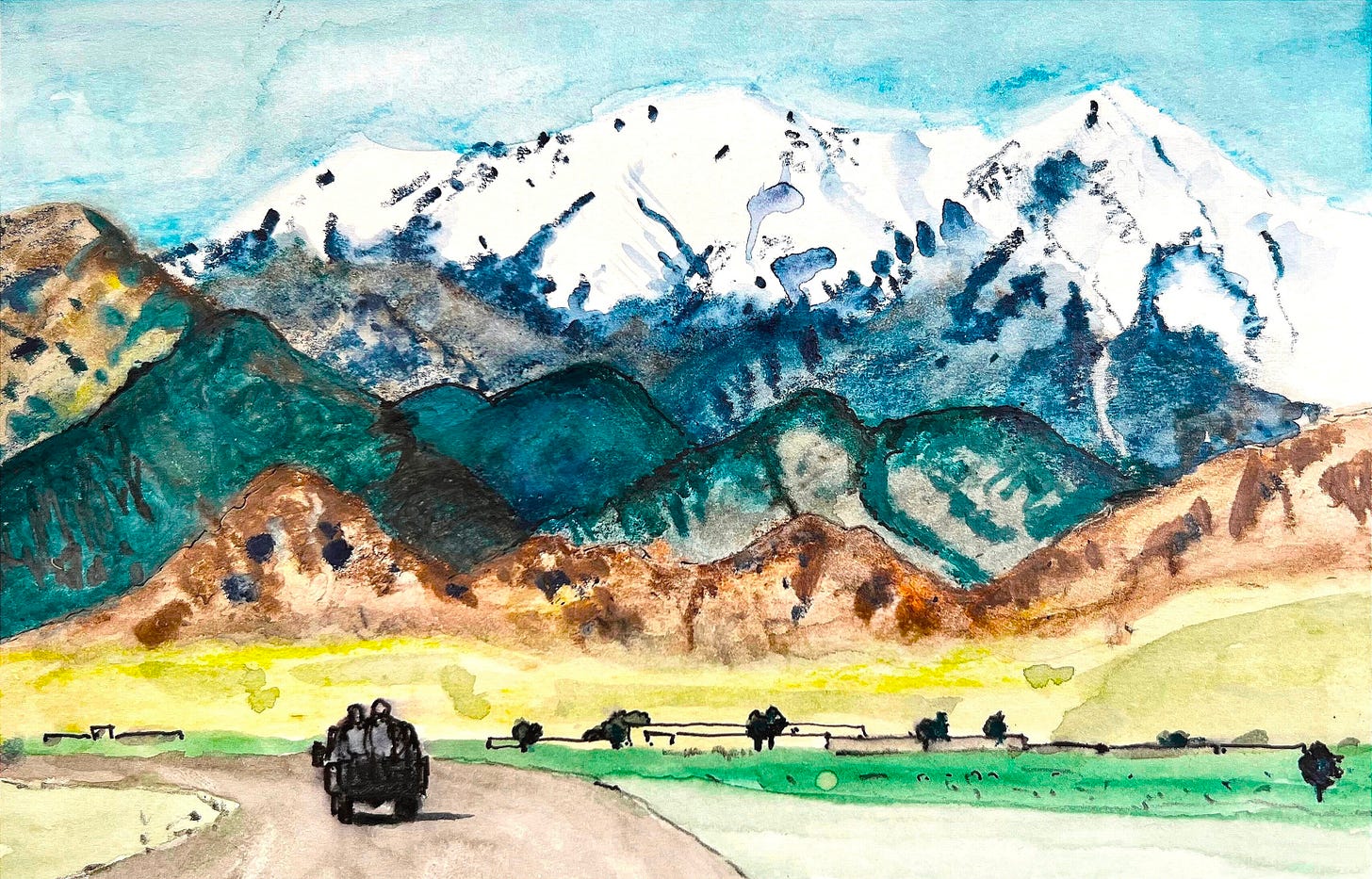

The Tora Bora hills in the eastern province of Nangarhar, overlooked by the Spin Ghar, or White Mountains. These wooded hills were the last known hiding place of Osama bin Laden, before he was tracked down and killed by US forces across the border in Pakistan in 2011.

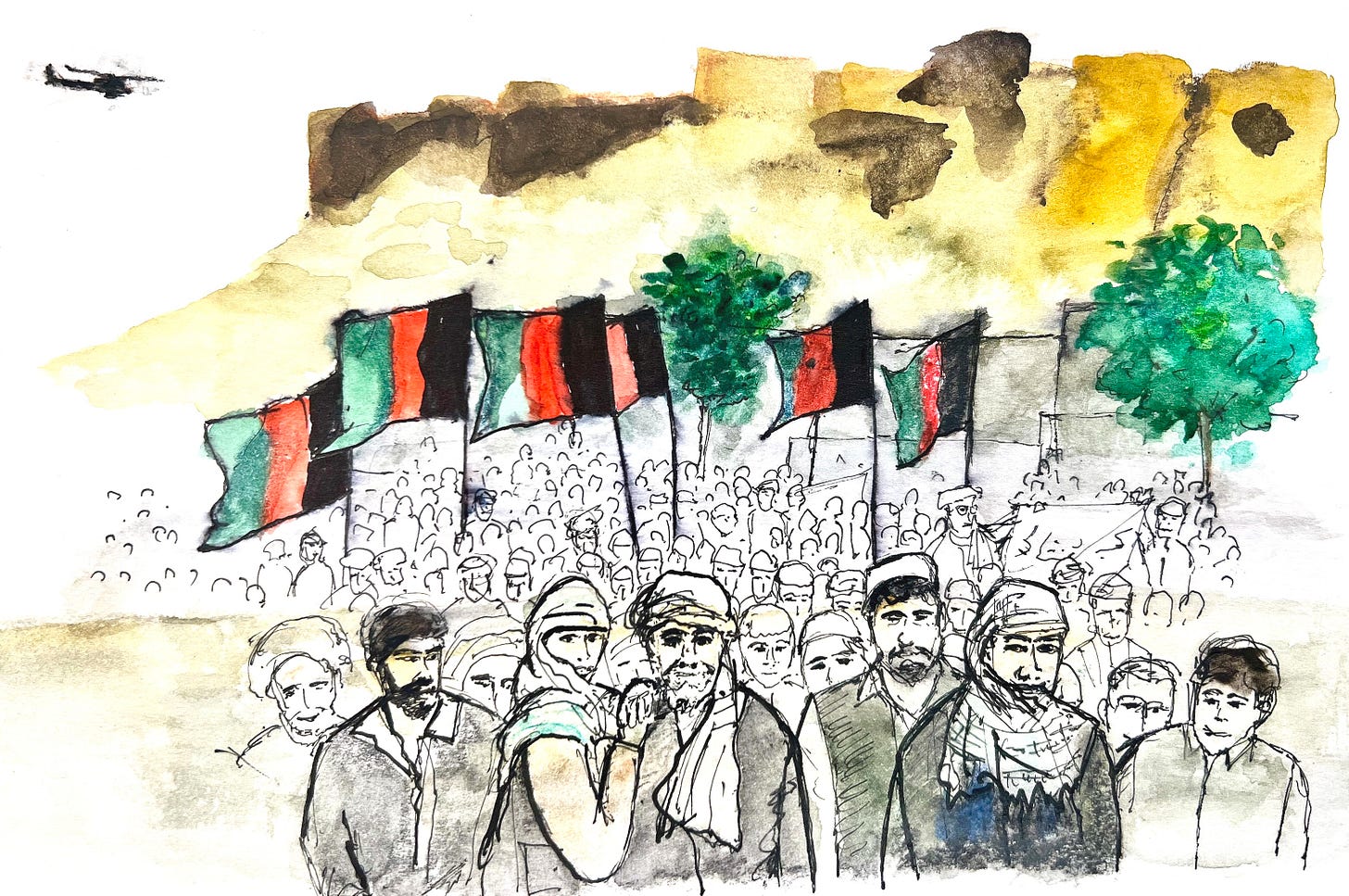

A snapshot of Afghanistan’s short-lived democracy. This was a scene during the 2004 presidential election, in the southern city of Ghazni, when Hamid Karzai was flown in under American guard for a carefully stage-managed rally.

History looked down from the ruins of the ancient citadel, dating back to the 11th century when the city was the capital of an empire encompassing most of contemporary Iran and northern India. After capturing the citadel in 1839, British colonial forces swept north and seized Kabul.

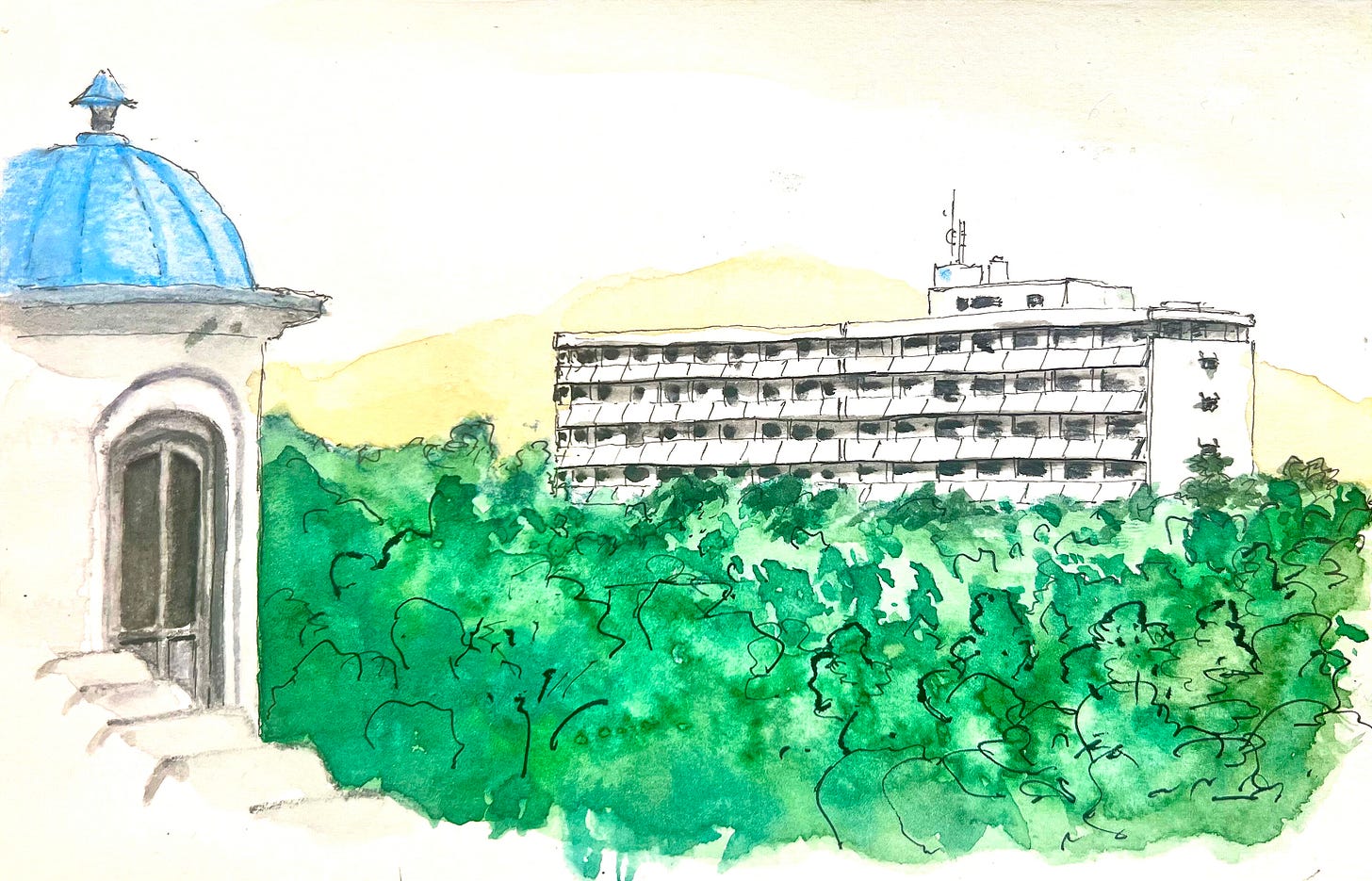

A snapshot of history in two buildings. The Intercontinental Hotel seen from the 19th century Bagh-e Bala (literally the ‘high garden’) palace in northwest Kabul.

Built by the eponymous British hotel chain in the 1960s, the ‘Intercon’ has been in the midst of Afghanistan’s tumultuous story ever since, sometimes hosting meetings and summits, sometimes mujahideen factions or Al Qaeda leaders, with regular periods as a battleground.

The nearby palace was built as the summer residence of the British-backed despot Abdul Rahman Khan, the so-called Iron Amir, who unified Afghanistan within its current borders. They put Khan in power in 1880 after invading Afghan territory for a second time, in case the Russian Empire got there first and threatened India, Britain’s prized colonial possession.

This could have been almost anywhere in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2021. But I did this drawing after watching US troops boarding a helicopter in the eastern province of Khost in 2005.

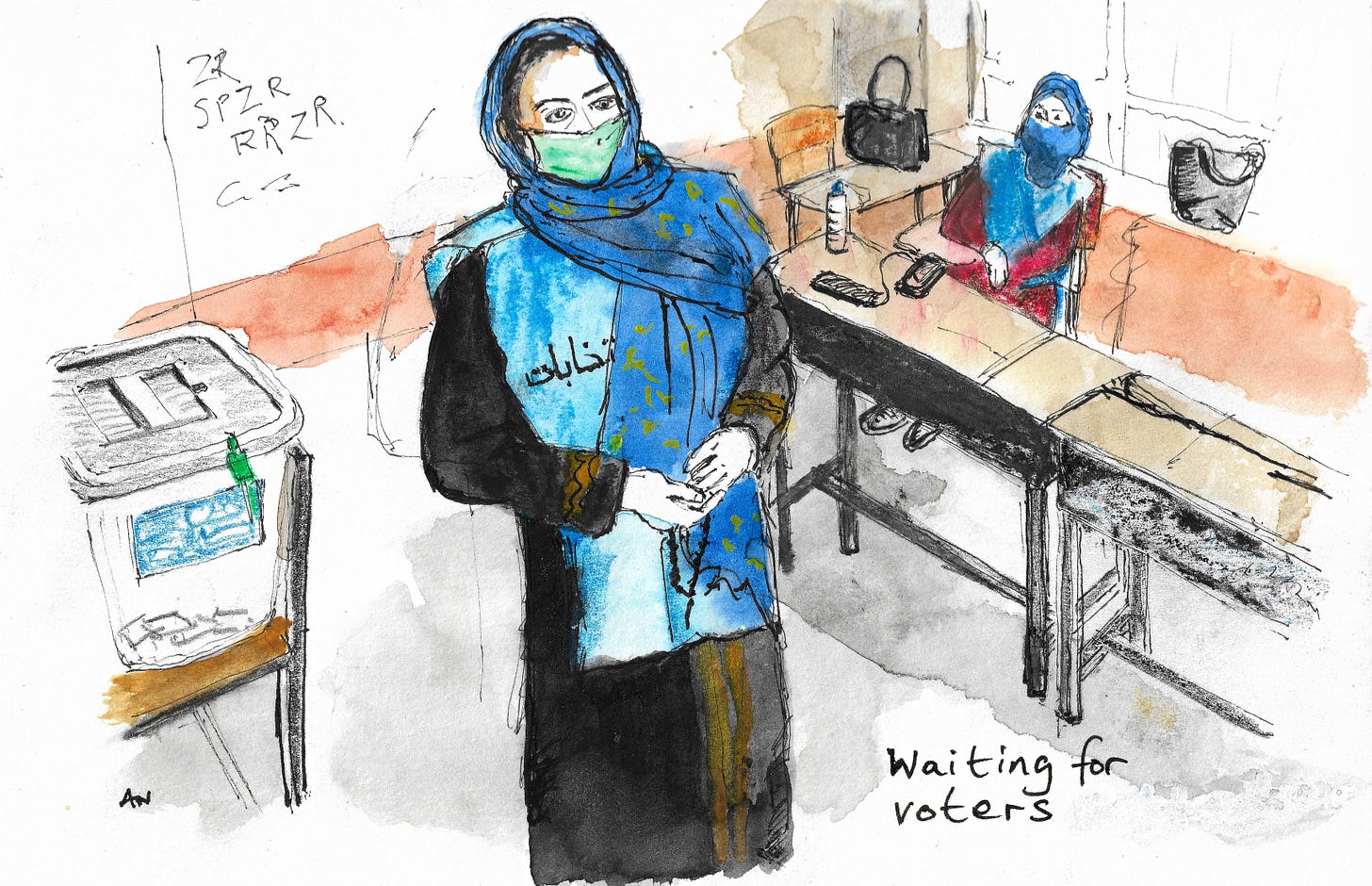

Afghanistan’s last presidential election in September 2019. I will always remember visiting this polling station in Charikar, a town about an hour’s drive north of Kabul. It had been quiet all day, the women working there said, reflecting what was a nationwide collapse in turnout—due partly to people’s fears of Taliban attack but much more because of a general disillusionment with the performance of their elected leaders and the democratic process.

This striking 2,000m mountain in the middle of Kabul has another name, but most people call it ‘Television Hill’ because of the forest of communications antennae that surmount it. During the civil war in the 1990s, it was used as a firing position by the mujahideen faction that secured it.

In 2019, I reported from Afghanistan’s western border with Iran on the growing number of people taking flight because of the deteriorating economy and security situation.

Every day, thousands of people, teenage boys among them, tried to make the crossing, hoping to make it to Europe. But many, if not most, were apprehended by Iranian security forces and sent back. I witnessed thousands being deported back to Afghanistan at the so-called ‘Zero Point’ line. Yet almost everyone I spoke to said they would try to make the journey again as soon as they could. And this circular process of flight and return continues today.

War & Peace & War: Twenty Years in Afghanistan was published in the UK in 2024 and is in US bookstores from late March onwards.

...real nice visual journalism, Andrew.

Remarkable illustrations. They say more than photographs.