Are we losing immunity—to ourselves?

Autoimmune disorders are becoming more common and wrecking lives

An outbreak of a rare and sometimes fatal autoimmune disorder which causes creeping paralysis has been making headlines in India over the past week.

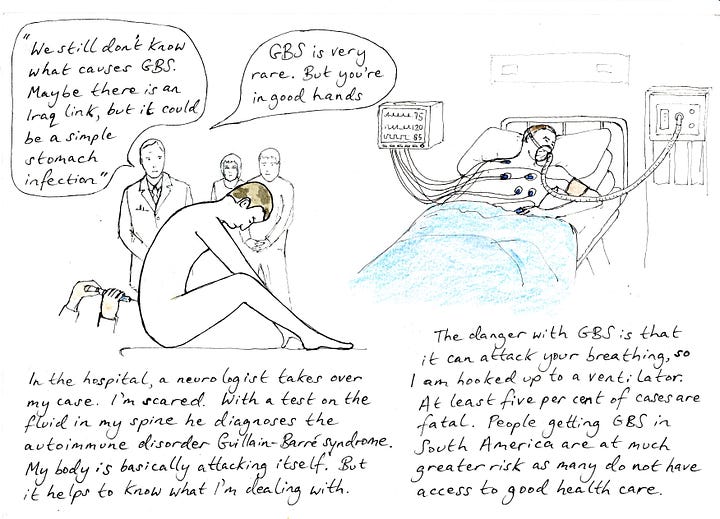

At least five people have died, including children, with dozens more in intensive care, after succumbing to what’s known as Guillain-Barré Syndrome, or GBS, in which the immune system malfunctions and attacks the body’s peripheral nerves.

Most of the 170 cases reported so far have been in the western city of Pune, but the disorder has also been tied to a child’s death far to the south.

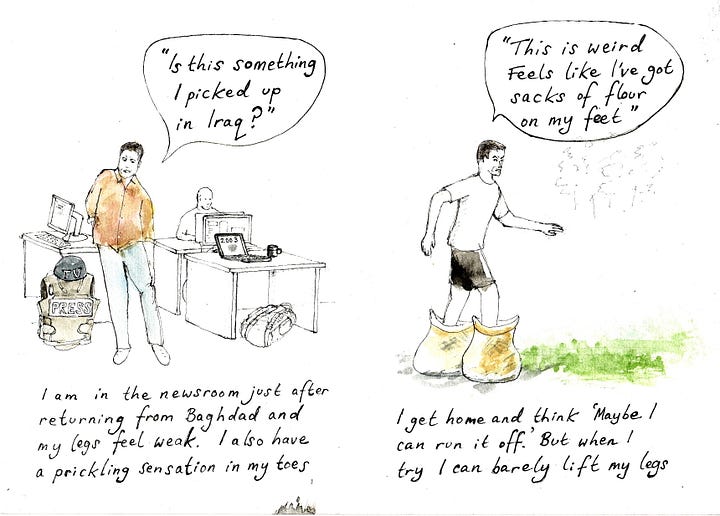

The reports caught my eye, because I once had GBS myself, more than 20 years ago.

It began with a feeling of weakness in my legs. But the doctor could find nothing wrong. A few days later, I was experiencing searing pain and struggling to walk, and talk, as my back and then my facial muscles seized up. Even swallowing was hard.

It was terrifying, not least because I had no idea what was wrong.

Thanks for being here. If you are not already, please consider subscribing to support my work. This post is free to read. For just $6 a month, you get all my writing and illustrations.

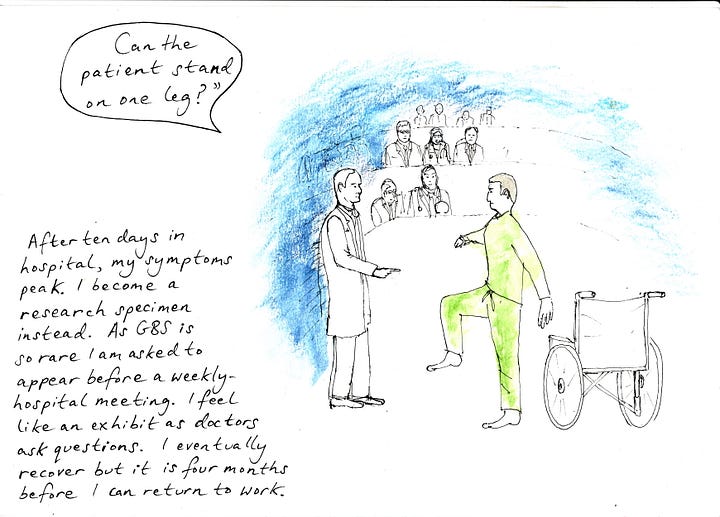

Baffled, my physician sent me to the nearest hospital, where I was diagnosed—and treated like a new species, because GBS was so rare. “You’re my first case,” the consultant said, barely concealing his excitement. “I’d only read about it before”.

There have been similar accounts from India, with one of the afflicted children initially complaining of being unable to hold a pen before being admitted to hospital days later in a state of almost total paralysis.

And there is no cure—though one treatment my consultant was considering was the equivalent of changing the oil in a car, to flush out my immune system and reboot it.

I was fortunate to avoid that.

After 10 days wired up to an array of monitors and a ventilator—because the misfiring immune system typically targets the function of lungs and other organs—my symptoms began to subside and I was discharged.

But it took months to recover and return to work—a common longterm effect of many autoimmune conditions.

When GBS briefly made the news in 2015-16, after a spike in cases in Brazil linked to an outbreak of Zika virus, I was asked to do this illustrated piece about my experience.

(You can read the full article on Narratively’s—paywalled—Substack, but here are the visuals.)

Coming back to the present, GBS is still fairly rare. And that is why what is still a relatively small caseload for a disease outbreak—especially in India, the world’s most populous country—is getting this kind of attention.

But the condition is becoming more prevalent worldwide.

And, crucially, it is part of a broader rise in what the medical profession calls ‘autoimmunity’, involving better known conditions such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and psoriasis.

At least 100 different types of autoimmune disorder have now been identified. And while their symptoms differ, they are grouped together because all involve the body’s immune system mistakenly attacking healthy tissues and organs.

According to the US National Health Council, as many as 50 million Americans may be suffering from autoimmune diseases, with case numbers rising 3-12 per cent a year.

“Autoimmunity is an epidemic,” warned an op-ed in Scientific American a little more than a year ago, the writers highlighting the devastating effects on peoples’ lives.

As a person’s own immune system attacks their body instead of microbes or cancerous cells, they can experience chronic fatigue, chronic pain, drug dependency, depression and social isolation. These symptoms annihilate mental health, wreck promising careers, destroy lives and, often, ruin families. For too many, these illnesses result in early death.

There is still no consensus on what exactly is causing this rise in autoimmunity.

But research suggests it is the result of a complex interplay between genetics and changes in our environment and lifestyles, including factors such as exposure to microplastics and other kinds of pollution, as well as diet and stress.

There are many threads to untangle, so more work needs to be done.

But American drugs companies have already cottoned on to the demand, offering up a deluge of cures for conditions such as psoriasis and arthritis in TV and online ads.

This all comes amid growing investment into techniques for prolonging our lives, spearheaded by billionaires such as Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel.

Perhaps they will succeed. But these longer lives may not be worth living unless we can also contain the surge in autoimmune disease.